Abracadabra: Language, Memory, Representation

Today's reading: Eco, Ch. 10

Words and Things and Things and Words.

Bacon

Francis Bacon's New Method

- The role of Chinese and Egyptian Characters

By "language" is meant a written representation of the world. Bacon was the first to suggest that the world needed a stable, universal, written script for the communication of scientific truth. He was less interested in the religious question of which language was the origincal perfect language, and more interested in the creation of an artificial one. - Metonymic vs. Metaphoric (Iconic)

substitution

Bacon was impressed with Chinese characters, and like Leibniz, suspected them of being radicals: of representing notions directly, rather than through speech (as in Latin). As spelling normalizes, Latin (and English) become more ideographic, words come to have a particular spelling, and therefore a stability taken to indicate a stable meaning. Ideographs are assumed to be Iconic/Metaphorical (they resemble or stand for the thing) vs Indexical/Metonymic (they point to the thing).

- The need for accurate accounts of observation: the

problem of ambiguity in words

Bacon was also obsessed with ambiguity in speech; the first part of the Novum Organum (New Method) is concerned with all the ways ambiguity enters language. (Aside:This point alone seems to suggest that Bacon did not write Shakespeare's works, given his disgust with ambiguity, metaphor, pun, inside jokes etc.)

- Bacon Identified several idola: The Idols of

The Tribe, The Cave, the Marketplace and the theatre. He

gave examples of the hopeless confusion of

common speech. (e.g. Slaughter p. 91-2).

- A new Method of observation would address this problem

accurate observations could be represented by accurate notions and then by accurate words. As opposed to the Aristotelian taxonomy which begins with categories and analyses everything in terms of them, Bacon would have observation inform our notions.

- This leads, naturally, to the question of completeness

How to have a complete language when the observation of nature is partial? His reply to this is that no general or universal language can be complete: science will remain an incomplete system until God wills otherwise. It cannot be perfect in a divine sense, but it can become ever more accurate.

Scientists and Scientific Languages

The growth of observation.

In the 16th and 17th century, there is obviously no shortage of new observations: Hooke and teh observation of cells, Boyle's Law of Gases, Galileo's Siderius Nuncias William Harvey's On the Motion of Heart and Blood in Animals, and many others. But there is no common language for all of them.

Between 1640 and 1700 about 20 or so attempts at a scientific language by people of varying stature: Jean Douet, Des Vallees, Jean Le Maine, Champagnolles, Philip Kinder, Reverend Jonson of Ireland, Bishop Godwin (Man in the Moon), Comenius (Orbis Pictus), Bermudo, Potter, Cave Beck, Francis Lodowyck, George Dalgarno, Cyprius Kinner, John Wilkins, Father Mersenne, Rene Descartes, Seth Ward, John Webster, GW Leibniz.

Amongst them the goals fell into three categories:

- utility (e.g. a universal language for communicating with anyone-- usually built on the notion of "root" words)

- Baconian (e.g. The identification of simple notions, or axiomatic words out of which a "perfect" language would be built)

- Taxonomic (e.g. a system either binomial, or hierarchically organized to encompass a mass of facts-- complete/incomplete)

Eco further distinguishes between "Encyclopedia" and "Dictionary"

- Encyclopedia amasses facts about a notion or thing.

- Dictionary attempts to give minimum possible facts that are necessary to distinguish it from all other entries.

Primitives and the organization of Content

To create an artificial language then, one needs two things: radicals (simple notions representing, in the case of Bacon, the simplest observed component of nature) and a system of characters, marks, signs, or pictures that capture the structure of the taxonomy that organizes the radicals.

Radicals

Some inventors started with natural language (e.g. Lodowyck below); others like Wilkins tried to start with observations of nature collected together and organized. One of the things that divide language projectors is whether they will classify everything that exists (all of the "accidents" in Aristotelian terms) or only the most essential components of all that exists (the "substance"). It is this opposition that leads to the constant destruction and renewal of taxonomic systems up to the present day.

Organization

Eco gives us several different kinds of orgainzation: the table of positive or negative differences, the hierarchy of differences and the Porphyrian tree in which each genus consists of opposites (rational/irrational) that determine the species.

Examples

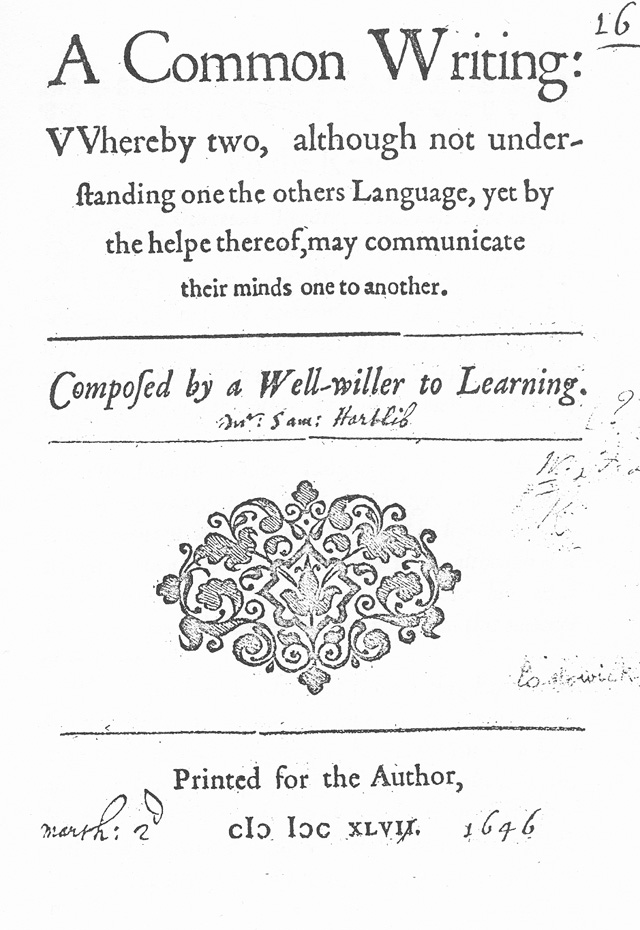

Example 1: Francis Lodowyck

A Common Writing (1647) Groundwork for a Perfect Langauge (1652)

- attempt to creat universal language (not perfect)

- Basic building blocks are "root" words

- a system of characters to represent root words.

- 1

- 2.1

- 2.2

- 3

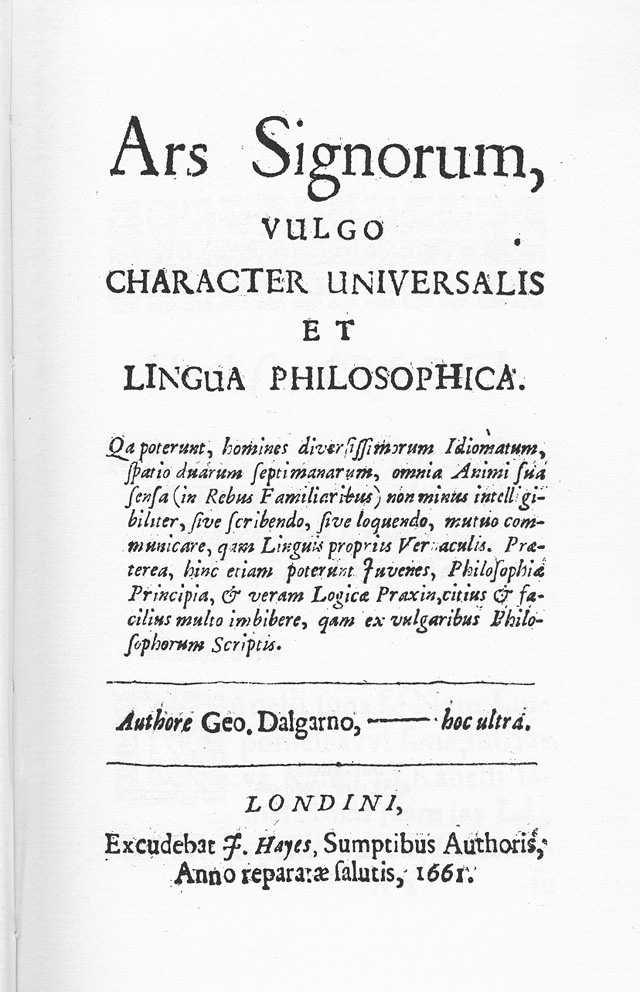

Example 2: George Dalgarno

- - Much more cryptic and allusive than the others.

- - More like a shorthand (a "tachygraphy") or a cryptography

- - Uses peculiar memory system to record root words.

- - Eco's explanation

Early English Books online Search Page.

Title Page to Lodowyck's Common Writing (1646)

Title Page to Dalgarno's Ars Signorum (1661)